Karl Barth Asks "Who Are We Becoming?"

Karl Barth challenges us to ask not just what we should do, but what truth requires of us—and whether we have the courage to bear witness to it, even when it costs us.

This post is part of a series on Moral Leadership.

The Moment We Face

I have really enjoyed writing this series on Moral Leadership. The two entries I’ve done so far have generated some of the most texts and emails I’ve received from readers. If I had to guess, it’s because moral leadership feels so absent right now. I didn’t write a piece for this series last week—partly because there has been a lot going on, but mostly because I needed to refresh myself on Barth.

I dove in pretty deep with Bonhoeffer. I loved re-reading his sermons and books. But for Barth, I confess, I had to dust off my seminary notebooks. I wanted to do this because of the reverence with which Bonhoeffer treated Barth. The more I revisited Barth, the more I felt confronted with how I was approaching my own attitude toward our current moment. So, with the delay of two weeks, I wanted to share some of what I found and why I felt tested.

I also want to make something clear: I know many who read this newsletter come from different faith traditions or have no faith at all. I welcome all of you. I’m not writing about these theologians to change anyone’s faith. I write about them because they have something urgent to tell us about the moment we are living in.

The greatest threats to democracy do not always come from violent coups or foreign adversaries. More often, they come from within—through slow erosion, through moral compromise, through the silence of those who should know better.

We have seen this before. We see it now. Institutions that once upheld the rule of law are bending. Leaders who once claimed to defend democracy now excuse its erosion. People who once spoke of principle now speak of realpolitik, choosing survival over truth.

There are those who tell us to be patient, to wait for a more opportune moment to speak. They say the stakes are too high, the costs of defiance too great. But history has already judged this excuse. When faced with rising authoritarianism, silence is not neutrality. It is surrender.

Karl Barth understood this. He saw how moral institutions—especially the church—could become complicit in the decay of democracy. He saw how people who should have been truth-tellers instead became justifiers, enablers, and rationalizers of evil. And he refused to be one of them.

Who Was Karl Barth?

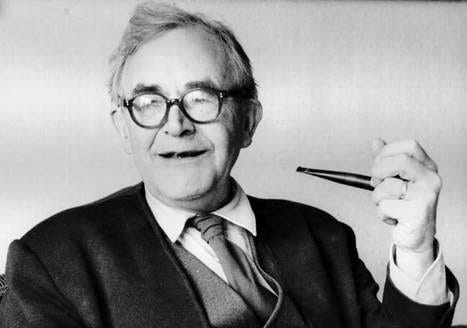

Karl Barth was one of the most significant theologians of the 20th century, a Swiss pastor who rose to prominence in Germany during a moment of national and moral crisis—the rise of Adolf Hitler.

In 1933, when Hitler seized power, many German churches fell in line. They accepted Hitler’s claim that Nazism and Christianity were compatible. The so-called “German Christians” movement sought to merge faith with nationalist ideology, declaring loyalty to Hitler as a Christian duty.

Barth saw this for what it was: a betrayal.

In 1934, he became the chief author of the Barmen Declaration, the most significant theological resistance to the Nazi regime. The document rejected any allegiance to a political leader over God. It condemned the church’s capitulation and insisted that truth was not something to be reshaped to fit the needs of the powerful.

For this act of defiance, Barth was removed from his university position and forced into exile. He was told to swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler. He refused. And so he was expelled from Germany.

But the words of the Barmen Declaration lived on. They became a rallying cry for the Confessing Church, the underground movement of German Christians who refused to bow to Hitler.

Barth did not stop the Nazi rise to power. He did not prevent the war. But he named the truth. And in doing so, he proved that even when institutions fail, even when moral leaders crumble, it is still possible to stand.

The Crisis of His Time—and Ours

Barth has this great phrase: “to be a Christian is to be called to Christ with others.” Faith is not a solitary pursuit but a communal one. That has major implications for how we think about moral leadership today.

Truth comes first. Barth insists that we do not start with what we ought to do, but with what has already been done. For him, that truth was revealed through Jesus on the cross—but whether one shares his faith or not, the core idea remains powerful: we are called to act not in isolation, but in community, accountable to something greater than ourselves.

From that revelation, our response should be gratitude, not compromise. This is the concept that confronted me the most. Barth warns that we should not act out of a sense that we are the moral exemplars or leaders. Instead, we should always be careful to reflect the teachings of Jesus. We don’t stand up against Trumpism or the evils unleashed by modern authoritarianism because we think it’s wrong. We stand up because that’s what Jesus would have done. We must stay accountable to principles greater than ourselves—whether we understand that as God, justice, human dignity, or the shared moral foundation that binds us together.

At its core, Barth’s message is that moral leadership is about bearing witness to truth, even when it is inconvenient or dangerous. It is not about standing against something simply because we disagree with it—it is about standing for what is right, because it is right. For Barth, this was rooted in Christ. For others, it may be rooted in a different but no less urgent conviction. What matters is the commitment to something beyond ourselves—the belief that truth exists, that it must be named, and that we are responsible for living by it.

This is where Barth’s critique of the church in Nazi Germany hits hardest. He did not just condemn those who actively supported Hitler. He condemned those who remained silent—those who adapted themselves to survive rather than standing firm for the truth. This insight is painfully relevant today.

Barth also offers a profound theme of hope through resistance. Hope, for Barth, is not passive optimism. It is not the belief that things will work out. Hope is the willingness to keep fighting for the truth because it has been revealed—even when success seems impossible. This ties directly into Václav Havel’s definition of hope that I wrote about in An Archipelago of Hope:

"Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously heading for success, but rather an ability to work for something because it is good."

This is perhaps my favorite insight from my seminary notes:

Barth’s Ethical Question: Who Are We Becoming?

Barth teaches that when engaging with others, we must always ask: Who am I becoming? And who is the person I engage with becoming? This idea challenges us to consider whether our compromises and pragmatism are making us better or leading us further from the truth.

What We Must Do

Barth’s example challenges us not just to hold convictions, but to name them. It is not enough to believe in democracy—we must defend it. It is not enough to see corruption—we must expose it. It is not enough to privately reject lies—we must publicly reject them.

So, what must we do?

Refuse to Accept the Normalization of Lies – Do not let dishonesty become routine. Do not let propaganda go unchallenged. When leaders distort reality, correct them—loudly.

Hold Institutions Accountable – If courts, churches, and public officials betray their own missions, call them to account. Silence is complicity.

Speak the Truth Even When It Costs You – Many today fear the personal cost of speaking out—losing status, losing friends, losing influence. Barth reminds us that truth is worth the price.

Ask Yourself

Where am I tempted to compromise truth for the sake of comfort or acceptance?

How do I challenge lies and distortions in my own circles of influence?

What is one specific truth I must name this week, even if it is unpopular?

Barth did not prevent the rise of fascism in Germany. But he named it for what it was. And in doing so, he showed that even in the worst of times, there is power in refusing to surrender to lies.

This is our task today. Not just to resist authoritarianism, but to insist on reality.

Next Week: James Baldwin and the Reckoning America Avoids

Karl Barth confronted the church’s moral failure in Nazi Germany. James Baldwin confronted America’s refusal to reckon with its own history. Next week, we will examine how Baldwin’s searing clarity still speaks to the crises we face today—and why we must tell the full truth about our past if we are to have any hope for the future.

We need to speak up or we become irrelevant.