James Baldwin and the Reckoning America Avoids

Real change begins with an unflinching reckoning—both with our history and with ourselves.

This post is part of a Maverick series on Moral Leadership.

Do We Really Want to Change?

America has never lacked prophets. It has lacked the will to listen.

For generations, this country has resisted the voices calling it to account. We tell ourselves stories of progress while avoiding the reckoning that real progress demands. We celebrate democracy while refusing to confront the forces that have undermined it from the beginning.

The temptation, in moments of crisis, is to believe that the threat we face is new. But the deeper truth—the harder truth—is that the crisis of democracy in 2025 is not just about Trumpism, or January 6, or the rise of authoritarian politics. It is about America’s long history of refusing to tell the truth about itself.

James Baldwin understood this better than most. He knew that the greatest danger to democracy was not just the open bigot or the demagogue, but the comfortable moderate—the one who refuses to see, who insists on illusions, who would rather preserve their own innocence than confront injustice.

And he warned us: “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Who Was James Baldwin?

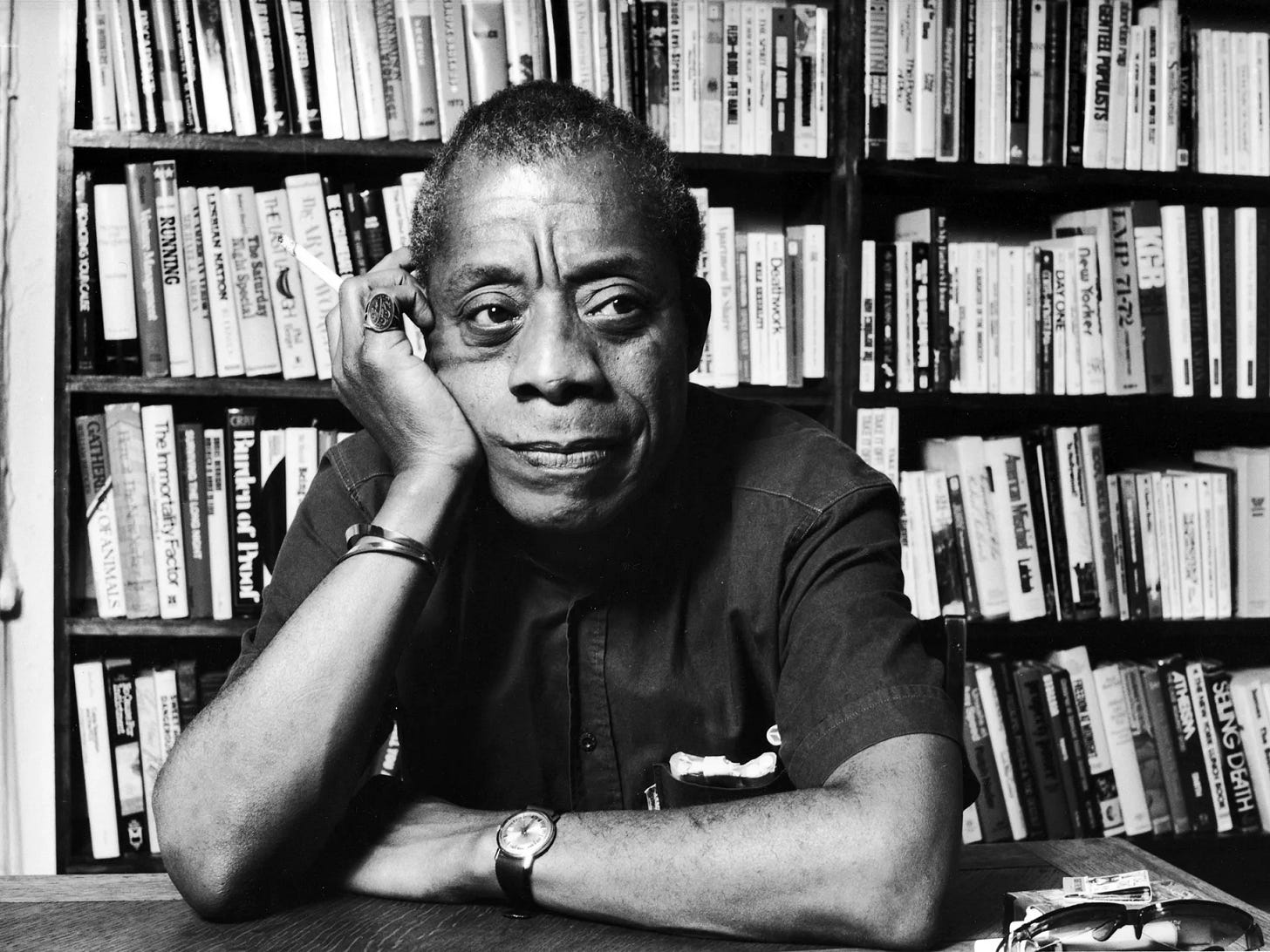

James Baldwin was one of the most brilliant and uncompromising moral voices in American history. A writer, essayist, and public intellectual, he spent his life telling the truth about America’s racial and political contradictions.

Born in Harlem in 1924, Baldwin grew up in a country that denied his full humanity. He saw how Black Americans were forced to fight for dignity at every turn. He saw how white Americans—especially well-meaning liberals—insisted that racial injustice was unfortunate but temporary, something that could be solved with patience rather than upheaval.

Baldwin was shaped by the Black church, mentored by the great preacher and activist Howard Thurman, and later, by his time living in exile in France, where he could see America more clearly from a distance. He wrote essays and novels that exposed not just the cruelty of racism, but the self-deception at the heart of American life.

His greatest works—The Fire Next Time, Nobody Knows My Name, Notes of a Native Son—were not just indictments of racism. They were indictments of moral failure. They demanded that America stop lying to itself.

And Baldwin was not just writing about race. He was writing about power, about the American tendency to ignore suffering in order to maintain the illusion of innocence. He was writing about the way people justify their silence in the face of injustice. He was writing about how a nation’s refusal to tell the truth will always, eventually, lead to crisis.

The Crisis of His Time—and Ours

Baldwin wrote in the 1960s, but he was writing about this moment too.

He saw how democracy could be hollowed out—not just through voter suppression or state violence, but through indifference. He warned that the great danger to America was not just hatred, but apathy.

That lesson has never been more relevant.

In 2025, American democracy is under siege—not just from those who openly seek its destruction, but from those who refuse to fight for its survival.

We see it in leaders who downplay the threats of authoritarianism.

We see it in moderates who say the fight is too messy, who long for civility over justice.

We see it in institutions that bend to power rather than holding power accountable.

We see it in the endless calls for patience, for gradualism, for waiting just a little longer for justice.

Baldwin had no patience for this.

"I can't believe what you say," he told America, "because I see what you do."

He knew that real change is not made by those who wait for a better time. It is made by those who force the issue—who make it impossible to ignore.

The Moral Question Before Us

Baldwin’s moral clarity came from his refusal to accept illusions. He understood that America’s problem was not ignorance—it was willful blindness. It was not that people didn’t know the truth; it was that they chose not to see it.

This remains our problem today.

The question is not whether we know what is happening. We know. We have seen the erosion of democratic norms. We have seen the way lies are repeated until they become truth. We have seen the retreat of moral leadership in the face of political pressure.

The question is: What will we do about it?

Baldwin reminds us that the work of moral leadership is not about comforting people. It is about disrupting them. It is about forcing people to confront what they would rather avoid.

"Precisely at the point when you begin to develop a conscience, you must find yourself at war with your society."

We must ask ourselves:

Where am I excusing inaction because I fear discomfort?

Where am I tempted to wait rather than to act?

Where am I avoiding hard conversations because they will cost me something?

Because Baldwin’s warning is clear: The greatest danger is not that injustice exists. The greatest danger is that people will adjust to it.

What We Must Do

Baldwin did not believe in false hope. He did not believe in easy solutions. But he believed in action. He believed in speaking truth when silence was easier. He believed in love—not as sentimentality, but as a force that demanded justice.

So what must we do?

Tell the Truth Relentlessly – Baldwin knew that the hardest thing to do is to make people see themselves as they are. But truth, no matter how uncomfortable, is the first step toward change.

Reject Complicity – Injustice does not need active support to thrive. It only needs people who look away. Do not be one of those people.

Do Not Be Afraid of Conflict – Baldwin knew that real change does not come through comfort. It comes through struggle. If you are fighting for democracy, for truth, for justice—expect resistance. That is the cost of the work.

Build Something New – Baldwin was skeptical of institutions that refused to change. He believed that sometimes, you have to build new structures rather than rehabilitate the old. If existing organizations and systems will not defend democracy, create alternatives.

Ask Yourself

Where am I accepting a lie because it is easier than confronting the truth?

How do I challenge apathy in my own community?

What is one thing I can do this week to force a conversation that needs to be had?

Baldwin did not live to see America fully reckon with its past. But he forced the conversation. He left behind a body of work that still challenges us—still haunts us—because it demands that we answer the same question he asked:

"Do I really want to be changed?"

Because that is the real question. Do we want justice, or just the appearance of it? Do we want to save democracy, or just lament its decline? Do we actually want to do the hard work of reform, or do we just want to seem like we do?

This is our task. Not just to see the crisis, but to act.

Not just to witness the moment, but to change it.

Next Week: Howard Thurman and the Inner Strength to Resist

James Baldwin confronted America’s refusal to tell the truth. Howard Thurman spoke to the exhaustion that comes from fighting for justice in a world that resists it. Next week, we will explore Thurman’s vision of spiritual resistance—how we sustain our moral courage when the fight feels endless, and how we cultivate the inner strength to keep going.

As a gay and black young man, Baldwin knew he had to leave the country he loved and spent much of his life outside the U.S. Many of our young and brilliant thinkers of this era might make a similar choice if opportunities and liberties disappear.

Thank you, Reed! This is fantastic!!